Cities need sunsets

If it's tough to catch a sunset in your city, it might be getting you down

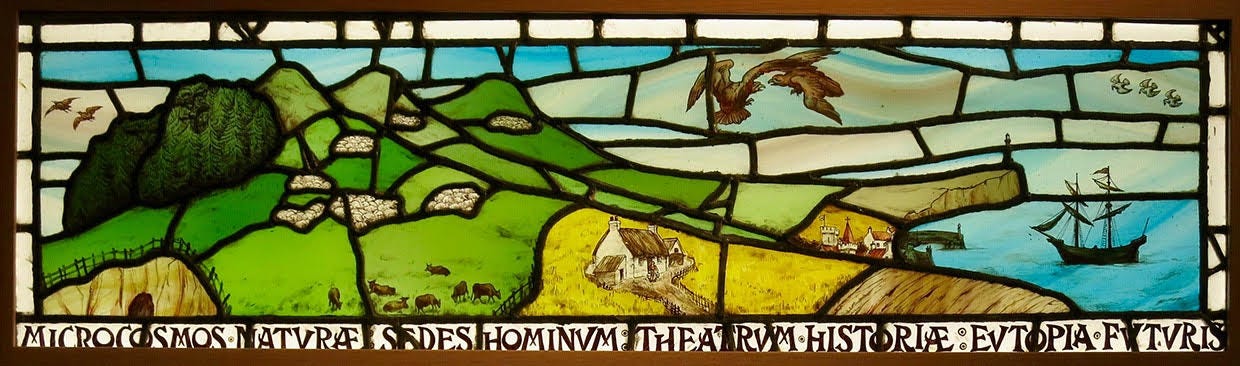

THE VALLEY SECTION, BY JOHN DUNCAN, FOR PATRICK GEDDES

So much in cities is hidden in plain sight. During a recent talk at Riddles Court, located on Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket (Royal Mile), I got to know someone I thought I already knew. Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), the patron saint of modern planning and the founder of this centre for the study of cities and social change, feels very much alive here. One of the stained glass plates he commissioned to illustrate his strikingly original ideas about cities was a centrepiece of that evening’s discussion. At a glance, “The Valley Section,” as it’s widely known, looks pretty enough: green hills, valleys and pastures sloping down to towns and ships on ocean shores. But it wasn’t until I had a good hard look at it, with the help of a historian, that I finally got what Geddes was saying: cities need nature.

That’s because people need nature, no matter where they are. In Edinburgh, that mostly means craigy, ageing mountains. Tourists and residents alike toil up and down its virtually unavoidable slopes and steps (the Old and New Towns), climb to the top of ancient volcanos (the Castle, Arthur’s Seat), or hike the Blackford Hill, among several others.

Iconic cities tend to have something unique about the natural feature they are known for. It’s glorified, not hidden. A river, for instance, might mean elaborate bridges and islands (Berlin), virtually every type of vessel, large and small (London), even swimming —hello Paris! Though made-made, canals are as various as their city’s architecture: think Amsterdam, Venice, Birmingham. And valleys, such as Toronto’s massive network of ravines, can wrap an otherwise ferocious case of urban sprawl in a park-like setting (although the vast majority of Toronto’s residents live too far away to get the daily benefit of these green corridors.)

But it got me thinking; what about cities that lack easily accessed natural landscapes? Because there are many. Large cities located on flat plains or where urban density and lack of planning vision puts the natural world beyond an easy walk. They need nature too.

One answer might be sunsets. Fair to say they are everywhere! And while it may happen every day, there’s still something profoundly moving about watching the sun dip low in the sky, its light seeming to intensify even as it loses strength. It reminds us of that eternal emblem of the planet, the horizon, and it draws a border between the two worlds of consciousness, light and dark. (Of course, sunrises do the same but most of us seem to miss those.) And it links us to others, who are also watching.

ISTANBUL, WITH THE BOSPHORUS STRAIT

What’s it like to live in a city where the full experience of a sunset can feel like a rarity? To me, it’s like living in a box. Or perhaps boxes is a better word. The interior box of the workplace, the exterior box of narrow streets lined with too many tall buildings that crowd out the sky, the box of home, with windows that look out onto other boxes.

What do our eyes and hearts miss in these cities? The list is endless: incandescent clouds, the curving outline of a hill, the sharp edges of a single, graceful building, the reflections that bounce off nearby prairie grasses, the glittering surface of a central city river. All are turned into theatre by sunsets. I can think of several mega-cities that have managed to limit their tall buildings and preserve open spaces — keeping, among other things, their sunsets. Think of the sun setting over Waterloo Bridge in (still mostly low-rise) London, made famous in the 60’s pop song, “Waterloo Sunset.” Then there are the famous sunset views along the Bosphorus Strait in Istanbul, historic mosques and palaces outlined in vivid detail. Even Manhattan, that steel and glass forest, offers fine sunsets from the vastness of Central Park, among several other venues in the city’s core.

Any city can embrace its sunsets.

How did we lose sight of this critical link to landscapes? And why? There are a bunch of reasons, but the cures are not that difficult. Learn to say ‘no,’ when developers propose high rises where they’re not needed. And they are seldom needed. Widen key city streets: sight lines along broad boulevards can be spectacular. Draw guard rails around large open spaces in city centres — if there are any left. The views from these places draw many a sunset addict.

POND WITH DUCK AND SKYSCRAPERS, CENTRAL PARK, MANHATTAN

I’m not sure we can even blame it on money: the most visited cities in the world (including those noted above) do an outstanding job of maintaining these crucial links between nature and the built environment. And their economies are booming.

The closest I can come to it is short-term thinking, lack of power and/or will at the municipal level, and, worst of all, public apathy.

Geddes knew that cities that don’t reflect their natural settings are barren places that dehumanise their inhabitants. So, if you haven’t seen a sunset lately, I invite you to partake. Maybe it’s hiding in plain sight. And if you can’t find one, contact your local councillor.

TOKYO, THE WORLD’S MOST POPULOUS CITY

You’re so right about the importance of maintaining a city’s connection to its natural surroundings. Just having spent a week in London, I can confirm that its fabulous parks and trees are an essential part of what makes it a great city!